Although many in the West associate the Middle East as being the main source of jihadism, deaths due to terrorism in sub-Saharan Africa have outpaced those in the Middle East for the past several years.

The Sahel region of Sub-Saharan Africa, in particular, has become the centre of global jihadism, with more than half of all deaths due to terrorism taking place there in 2023. Jihadists have taken advantage of weak governments, ethnic divisions, and porous borders to expand their presence in the region, especially in the central Sahel sub-region, comprising Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso, where jihadists now control large swathes of territory.

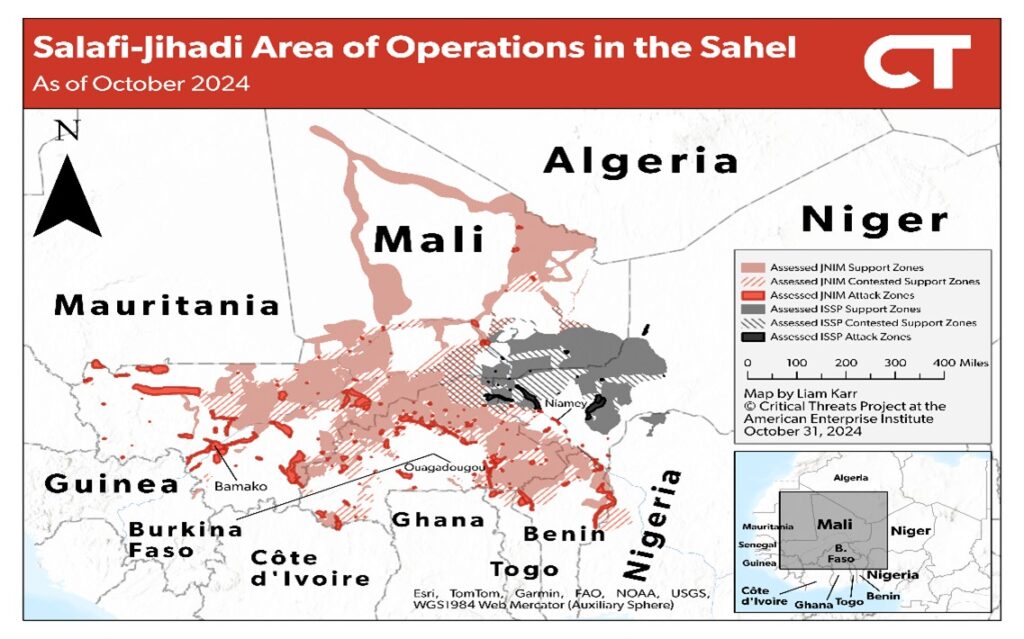

Two main jihadist groups vie for power in the Central Sahel: Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) – an umbrella organisation of al-Qaeda-affiliated groups – and the Islamic State Sahel Province (ISSP) – a wilayah of the Islamic State. ISSP mainly operates in the border region between Niger and Mali, where it has launched a campaign of violent conquest, resulting in widespread civilian casualties. Unlike ISSP, JNIM tries to limit civilian casualties to avoid alienating local populations and often attempts to negotiate with local leaders when assuming control over an area. Of course, these negotiations take place against a backdrop of coercion, kidnapping, and violence against collaborators, so they cannot be considered ‘peaceful’. Nevertheless, JNIM’s strategy of civilian engagement combined with the threat of violence has allowed it to consolidate control over large areas of Mali and Burkina Faso.

Following the departure of French forces, ISSP made rapid gains in Mali, taking control of almost the entire Ménaka region except the regional capital. It also launched an ambush against Nigerien security forces in October 2023, that reportedly killed over a hundred Nigerien soldiers. In July of 2024, following the seizure of Kidal, Malian and Russian forces attempted to push further towards the Algerian border but were ambushed by JNIM fighters who killed over 50 Wagner Group mercenaries and dozens of Malian soldiers. JNIM has also shown an ability to conduct sophisticated attacks, including striking Mali’s main military airbase and a gendarmerie training school near Mali’s capital, Bamako, in September 2024, killing at least 60 and burning the presidential jet. Beyond large-scale attacks and battles, ISSP and JNIM continue a steady pace of smaller-scale ambushes against state security forces and Russian paramilitaries, such as a JNIM ambush of Russian paramilitary forces in Central Mali on Nov. 22nd that killed seven. While it is too early to see the full effects of Russian intervention and the rise of military governments, at the present moment, jihadist groups remain a durable force in the central Sahel and continue to hold considerable territory.

As jihadist groups secure their position in the central Sahel, there is a high risk of their insurgencies expanding into neighbouring countries. JNIM has recently conducted attacks in countries neighbouring the central Sahel, such as Côte d’Ivoire, Benin, and Togo, and has even managed to establish limited influence in some areas of northern Benin and Togo. Benin alone saw over 170 attacks in 2023 by jihadist groups. While it has not yet attacked Ghana, JNIM fighters have been seen crossing the border to regroup and procure supplies. Additionally, JNIM-affiliated preachers from Burkina Faso have crossed the border into Ghana and preached in Muslim towns in the north of the country. ISSP, on the other hand, has conducted only minor attacks, such as raids into Benin, outside of its core base of operations on the Mali-Niger border. Its fighters, however, have been spotted using areas of northern Nigeria to regroup.

Thus far, JNIM has conducted attacks in neighbouring states but has yet to put down roots and recruit significantly from their populations. However, jihadist groups in the Sahel have proven their ability to adapt their communication strategies to specific local ethnic and economic contexts – as their influence expands, they are likely to localize their communications to play on the grievances of Muslim or Fulani communities in Côte d’Ivoire, Benin, Togo, and Ghana. JNIM is most likely to localize itself in countries with weak governance and greater social and economic divisions, such as Togo or Benin, rather than Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, which have strong economies and stable governments. Already, there have been reports of limited local recruitment in Benin and Togo, and JNIM will likely attempt to further recruit from Muslim border communities in these countries. If JNIM is successful at recruiting at a wider scale, these countries could see the rise of indigenous insurgencies of their own.

Another threat lies in the full collapse of the Malian, Nigerien, or Burkinabe governments. Of these, Burkina Faso is the most fragile. The Burkinabe government controls only about half of its territory, with JNIM controlling roughly 40% and ISSP controlling a small portion. Its military has been disorganized and faces a morale crisis, limiting its combat effectiveness. JNIM has also seized territory close to the capital, Ouagadougou, posing an existential threat to the government.

The collapse of the Burkina government represents a worst-case scenario. It would allow jihadists to use the country as a safe haven to continue attacks on Mali and Niger, as well as further expand into the coastal West African countries. Moreover, it would be a significant victory for jihadists that would likely become a central topic of jihadist propaganda, particularly for al-Qaeda, given that JNIM would be the most likely group to overthrow the Burkinabe government. This could galvanize supporters in other countries and lead to an influx of foreign fighters.

A small number of foreigners, mainly from North Africa and Europe, have come to the central Sahel to join jihadist groups. However, thus far, jihadist propaganda from the region has not made attracting foreign recruits a central theme. If jihadists manage to fully take over a country in the central Sahel, IS and al-Qaeda digital propaganda may call its followers to migrate to the Sahel, as they have done in other geographies. Over the last decade, more than 50,000 foreign fighters travelled to Iraq, Syria, or Libya to join the Islamic State, and al-Qaeda has recently called on its sympathizers to migrate to Afghanistan. If Burkina Faso or another regional government collapses, it could become a turning point for jihadism in the central Sahel and a rallying cry for jihadists across the world. The internationalization of jihadist insurgencies in the Sahel would represent a significant change that would greatly increase the threat to neighbouring countries, as well as possibly to Europe or the US.

While events in the region are still in flux, the threat from jihadist insurgencies in the central Sahel should not be underestimated. Thus far, the military governments and Russian paramilitary forces have failed to disrupt jihadists’ activities significantly, and jihadists continue to expand their footprint in the region. There is a tangible risk of jihadist insurgencies expanding into neighbouring countries and/or a regional government partially or fully collapsing. Without a significant shift in the trajectory of the conflict, jihadist insurgencies in the central Sahel can be expected to gain strength as the security situation further deteriorates.