The world’s attention to the war in Syria is allowing jihadist groups to change their narrative, by disguising their intents behind a false image built around humanitarian aid or struggle against war criminals oppressing innocent people.

This is potentially giving terrorist organizations and their sympathizers the chance to widen the heterogeneity of their affiliates by globally leveraging through the internet on the atrocities and injustice brought by the war, overlapping issues exclusively concerning violent extremism or radicalization.

In economic terms, this branch of the global jihadist web communication strategy is translating into a growing number of apparently decentralized (i.e. carried out by individuals or small groups) crowdfunding campaigns accepting bitcoin for either explicit militaristic or charity purposes.

These campaigns are very numerous and are generating more and more difficulties either in how to identify their real intent (if terrorist related or just scams) and in tracking down the total amount of funds received.

Indeed, on Telegram, these calls for donations are usually only advertised by explicit jihadist chat groups without ever interacting directly with them; create mirror groups to avoid the risk of being blocked or tracked; provide several donation methods (e.g. PayPal, fundraising platforms on the public web, various bitcoin addresses).

In order to better explain this trend, the following analysis will focus on a few topic cases related to this opaque calls for bitcoin, as Sadaqa al-Kahir and al-Ikhwa, self-proclaimed charity groups aimed at giving aid in Syria, and al-Sadaqa, a jihadist campaign raising money to support the mujahideen and some of the bitcoin addresses and transactions processed to finance these groups.

Binance bitcoin address (…bu1s)

Before deepening into the analysis of these campaigns, is worth doing a short explanation on the bitcoin address “…bu1s” (last four characters of the bitcoin address), which is where the most majority of the donations that will be traced are sent.

As explained by Bellingcat[1] and Cointelegraph[2], this address belongs to Binance, a very well-known crypto exchange service, which allows users to trade cryptocurrencies for fiat money or other digital currencies. In particular, it was discovered that this exchange service has been used to send bitcoin to Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades, the military wing of Hamas[3].

This doesn’t mean or proves at all a direct implication of the exchange service in terrorism financing, but it only means that these funds have been exchanged (after a few steps) into cash or other digital currencies by exploiting Binance.

The transactions of these campaigns, usually, before reaching Binance bitcoin address, made a donation to other bitcoin addresses. These bitcoin addresses may belong either to other exchange services working as middlemen between the crowdfunding campaign and Binance or could belong to a mixing service (to disguise the sender and the receiver)[4], to launder and hide the bitcoin donated before being cashed through Binance, or could also belong to private parties involved in this pattern.

Below, a description of each campaign and of some of the most significant transactions analyzed.

Al-Sadaqah Donation Campaign (… Nwpf, …qLez)

Since November 2017 al-Sadaqah (the charity) organization, began a still ongoing fundraising campaign on Telegram, other social media such as Twitter, and on the deep web[5] to raise bitcoin from Western supporters. The explicit intent of the call for bitcoin is to finance the mujahideen fighting against the Assad regime in northeastern Syria[6]. Nowadays, the organization’s Twitter page has been shut down, but its English and French Telegram accounts are still online.

The campaign seems not to be very popular. The BTC address advertised on al-Sadaqah, “… Nwpf”, shows that from November 2017 until its last donation on October 28, 2018, has received an amount equivalent to more or less $1,000 and processed 8 transactions (4 inputs and 4 outputs). Although most of the transfers were only worth a few dollars, one Bitcoin wallet from which a transaction was made to the wallet of Al-Sadaqa stood out …85oC, which has totally received the equivalent of more or less $7millions.[7] This Bitcoin wallet was associated with the kidnapping of a child in South Africa in May 2018 and many frauds.[8]

The wallet linked to the jihadist donation campaign[9] includes also another address “…qLez” (total received roughly $150).

Going backward from the only one donation received by this address, it appears that small amount of bitcoin (a few hundred dollars) has been transferred from one bitcoin address to another and all of them have only one input and one output. The interesting data is that the more we go back to the source of the only donation made to …qLez, the more we encounter an increasing number of wealthy bitcoin addresses (as FkdG), worth the equivalent of thousands of hundred dollars.

Given that these addresses belong to e-wallets with only one bitcoin address[10], they’re likely to belong to private wealthy donors rather than to any crypto-exchange or trading platform.

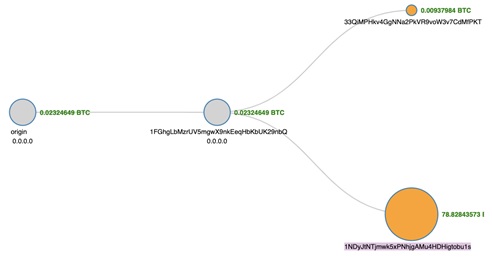

About the outputs of al-Sadaqa BTC addressees, the amount of bitcoin that their call for donations raised has been donated in full and, 4 out of these 5 outputs, as to “…nbQ” – “…WFDD8” – “…Xt6D”, carry out the same method to send their bitcoin to Binance wallet address:

- They periodically receive small amounts (from a few hundred to $1.500) from different BTC addresses.

- Then, that same day or the very next day, they do a multiple input transaction: send the small amount received to another bitcoin address and a larger amount (until $1 million) always to “…bu1s“, i.e. Binance (the big orange dot in the picture below).

These first wallets, where the donations are directly made by al-Sadaqa, could not belong to any private receiver but, given the incredible amount of bitcoin addresses owned by their e-wallets, are very likely to belong to an exchange platform or a bitcoin tumbler (a mixing service).

Humanitarian aid requests advertised on independent jihadist Telegram groups: al-Khair charity group and al-Ikhwa

As previously mentioned, not only explicit jihadist campaigns are calling for bitcoin donations for Syria, but also independent self-proclaimed charity groups.

Al-Ikhwa (The Brothers) and Sadaqa al-Khair present themselves as non-profit organizations, which are collecting donations to help the Syrian population, soliciting money also via Bitcoin to support widows and orphans.[11]

They both made their first appearance on Telegram more or less one year ago, posting extreme war images and video, in English and German, of armed attacks against civilians and of their initiatives to give aid to the Muslim people in Syria. Furthermore, both of these crowdfunding humanitarian campaigns declare on their Telegram and Facebook pages that they prefer to use alternative and anonymous fundraising methods because the conventional banking system or non-anonymous ways to receive and call for donations are already preventing them from processing any sort of payment (i.e. donorbox.com or wire transfers). Indeed, in order to help the needy and avoid authorities controls, they’re calling for donations via Paypal, money transfers, some crowdfunding platform on the clear web, and also in bitcoin.

Both of these charity campaigns have been advertised by Telegram chat groups which post explicit jihadist material, that have sponsored bitcoin donations to help the mujahideen by supporting military groups and crowdfunding campaigns as the Malhama Tactical Team (private military contractor team working exclusively for jihadist groups)[12] and SadaqaCoins (a cryptocurrencies crowdfunding website on the deep web, aimed at funding the mujahideen in Syria).[13] Even though most of these groups have among a few hundred to 2000 subscribers, their contents have been viewed by thousands of users. Some of these Telegram groups also promote the use of bitcoins by sharing self-made user’s manuals and explain the reasons why it is right to use cryptocurrencies according to the Sharia.

Both of these charity campaigns have been advertised by Telegram chat groups which post explicit jihadist material, that have sponsored bitcoin donations to help the mujahideen by supporting military groups and crowdfunding campaigns as the Malhama Tactical Team (private military contractor team working exclusively for jihadist groups)[12] and SadaqaCoins (a cryptocurrencies crowdfunding website on the deep web, aimed at funding the mujahideen in Syria).[13] Even though most of these groups have among a few hundred to 2000 subscribers, their contents have been viewed by thousands of users. Some of these Telegram groups also promote the use of bitcoins by sharing self-made user’s manuals and explain the reasons why it is right to use cryptocurrencies according to the Sharia.

In terms of donations, It seems that this communication strategy is already paying off.

Sadaqa al-Khair charity group: …51u7

In a few days (from May 21, 2019, until May 30, 2019) al-Khair BTC address …51u7, at the time of writing, shows a total of 6 transactions (3 inputs and 3 outputs) and a total received of more or less the equivalent of $1,100.

After a few days, the charity group didn’t publicly provide anymore its bitcoin address. Thus, it is possible that they’re providing a new bitcoin address on a private chat in order to avoid being detected.

All of the funds received have been transferred to other bitcoin addresses …MUaC (once) and …pXai (twice).

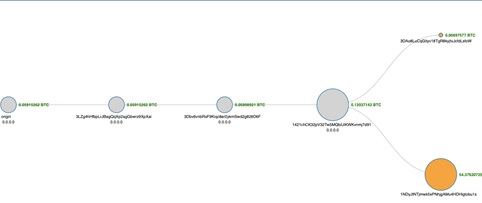

Also, in this case, there is a common pattern which leads to …bu1s, Binance, very similar to the one seen in al-Sadaqa, adding a few steps more.

In fact, the donations made by the al-Khair charity group, are firstly passing through two or three brand new BTC addresses, with two transactions each, at most, in order to be subsequently transferred to wealthier wallets which in the end move their funds to …bu1s (the big orange dot in the picture below)[14]

Same as in al-Sadaqa, the transfers involving BTC addresses which seem to be owned by private donors is made in the first or the second step of this chain. Thus, it is more likely that the most wealthy bitcoin wallets involved in these specific donations already belong to Binance or to another exchange service/mixing service which uses Binance to exchange cryptocurrencies. Hence, it seems that this campaign is not directly involving any wealthy donor.

Al-Ikhwa Independent Charity (several BTC addresses)

The al-Ikhwa crowdfunding campaign is using different bitcoin public addresses that, after the first four months of activities (since November 2018), have been monthly updated on their Telegram group in rotation. (…6p6S …Vgea …zcHH …deKc …8ELo …AU5j …XLRs …zXyz …zcHH). Starting since July 2018 the self-proclaimed charity group has received, ignoring non-public bitcoin addresses provided only through the private chat, a total amount of more or less $3000. The charity campaign received its first donation on …zcHH on March 2019 and the last donations have been received at the beginning of June 2019.

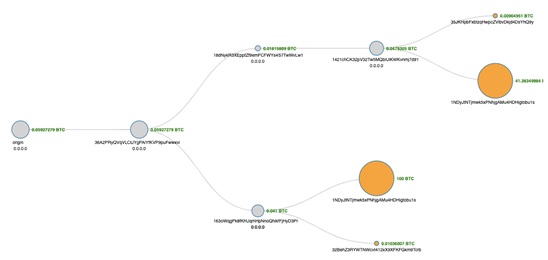

Many of these addresses belong to the same bitcoin wallet[15], and in some cases have been used to send a multiple inputs (a donation made simultaneously from different bitcoin addresses to one or many other wallets) of more or less totally $700 to …wwxi. [16]

This donation was then split into two different transactions: one is more likely to already belong to an exchange service/mixing service (its wallet has 108.496 total addresses) and then transferred to …bu1s. Then, the other donation was sent to another bitcoin address with a total amount received of $200 in 1 input and 1 output which then repeated the same process seen before to reach Binance bitcoin address[17] (the bigger orange dots in the picture below).

This process is repeated in almost all the bitcoin transferred by al-Ikhwa campaign to other bitcoin addresses until Binance.

Summary

As opposed to Hamas bitcoin crowdfunding campaign, in these cases the exploitation of Binance is related to the final output, meaning that the money received could be directly exchanged or used to finance other e-wallets.

This analysis explained the modus operandi of only a very limited number of the BTC addresses involved in these crowdfunding campaigns. Indeed, there are many others either wealthy or relatively poor addresses operating through this pattern, which bring out a very complex and solid network.

Hence, it is possible to highlight the following main aspects:

- It is still crucial to introduce stricter and updated Know Your Customer and Anti Money Laundering policies to exchange or purchase even small amounts of bitcoin (less than the equivalent $2000). Binance has already updated its account verification process, with the mandatory request of providing a valuable ID (e.g. National Identification Card, Permanent Residence Card, International Passport) even though, it is still not specified if there’s a minimum expense required by the user to be obliged to pass this identification process[18]. Nevertheless, there are still many others exchange or mixing services available which still don’t require, at the time of writing, any information about their users to purchase, receive or send either small or big amounts of digital currencies. This current situation allows the exploitation of digital money-mules or mixing services which can still easily scramble and hide an illegitimate transaction.

- Opaque humanitarian calls for anonymous donations may increase the difficulty to evaluate if there’s a nexus between their charity fundraising campaigns and terrorism financing by making more and more unclear which one is reliable (e.g. moved by a legitimate purpose) or connected to a jihadist group (as a smokescreen to disguise terrorism financing or money laundering) or just a major scam. In the cases of Sadaqa al-Khair and al-Ikhwa, being advertised and supported by explicit jihadist Telegram chat groups could mean both that they support a jihadist group and that they are just a fraud. In both cases, the fact that they are able to freely ask, send and receive bitcoins should be stopped just in the same way it already happens when they try to exploit the conventional banking system or public and legitimate crowdfunding websites.

- Crowdfunding campaigns as al-Sadaqa, al-Khair and al-Ikhwa don’t seem to have received huge amounts of bitcoin but this doesn’t necessarily mean that they can’t be a part of a wider network. Cases like these are becoming more and more frequent since 2017: they ask for bitcoin in order to help the Muslim Syrian population either by arming them to fight against the Assad and Western governments or by giving aid to the orphans or widows; they receive an amount in bitcoin in a range from roughly $1.000 to $3.000; they usually operate for more or less a year. They could act as digital-money mules or bitcoin tumblers, transferring from time to time small amounts of bitcoin through an infinite number of e-wallets, in order to let wealthy jihad supporters to be disguised and act unopposed while moving huger amounts of wealth globally and anonymously through them. In this case, they could have the double role of being a smokescreen (able to hide wealthier transactions) and a fundamental tactical role in facilitating terrorism financing.

[1] B. Smith (March 26, 2019) How To Track Illegal Funding Campaigns Via Cryptocurrency. Bellingcat. https://www.bellingcat.com/resources/how-tos/2019/03/26/how-to-track-illegal-funding-campaigns-via-cryptocurrency/

[2] https://cointelegraph.com/news/binance-vs-mcafee-hack-rumors-refuted-cryptocurrency-trading-resumed

[3] D.M. Barone (February 06, 2019) Hamas crowdfunding bitcoin: legitimizing cryptocurrencies from a jihadist perspective. ITSTIME https://www.itstime.it/w/hamas-crowdfunding-bitcoin-legitimizing-cryptocurrencies-from-a-jihadist-perspective-by-daniele-maria-barone/

[4] https://cryptalker.com/bitcoin-mixer/

[5] http://cjlab.memri.org/latest-reports/online-campaign-in-english-raising-funds-for-the-jihad-in-syria-in-bitcoin/

[6] http://www.sicurezzaterrorismosocieta.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Daniele-Maria-Barone-Jihadists%E2%80%99-use-of-cryptocurrencies_undetectable-ways-to-finance-terrorism.pdf

[7] N. Liv (July 2019) Jihadists’ Use of Virtual Currency 2. International Institute for Counter Terrorism ICT. https://www.ict.org.il/images/Jihadists%20use%20of%20virtual%20currency%202.pdf

[8] B. Strick (June 18, 2018) Tracing a Jihadi cell, kidnappers and a scammer using the blockchain — an open source investigation. Medium. https://medium.com/@benjamindbrown/tracing-syrian-cell-kidnappers-scammers-finances-through-blockchain-e9c52fb6127d

[9] https://www.walletexplorer.com/wallet/ae0f2ea8de2764e9/addresses

[10] https://www.walletexplorer.com/wallet/6402b0d863591976/addresses

[11]https://www.memri.org/jttm/charity-group-telegram-solicits-money-bitcoin-%E2%80%8Esupports-syrian-fighters-wives-martyrs%E2%80%8E

[12] D.M. Barone (December 01, 2018) Jihad as a Business Segment: the Malhama Tactical Team. ITSTIME. https://www.itstime.it/w/jihad-as-a-business-segment-the-malhama-tactical-team-by-daniele-maria-barone/

[13] N. Liv (July 2019) Jihadists’ Use of Virtual Currency 2. International Institute for Counter Terrorism ICT. https://www.ict.org.il/images/Jihadists%20use%20of%20virtual%20currency%202.pdf

[14] https://www.blockchain.com/it/btc/tree/453240296

[15] https://www.walletexplorer.com/wallet/3bfee78719643a94/addresses

[16] https://www.blockchain.com/it/btc/tx/7ad7c55e8724e9db3ca54651a3d7ab0591c93ce2bc0e5c39f97d09f09df8cc7d

[17] https://www.blockchain.com/it/btc/tree/431361274

[18] https://support.binance.je/hc/en-us/articles/360020832652-How-to-Complete-the-Account-Verification-KYC-Process