In Yemen, the intra-jihadi rivalry between al-Qa’ida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and local cells of the so-called Islamic State has been gaining momentum, exacerbated by the ongoing multilayered conflict in the country. Since the beginning of the crisis, jihadi networks were able to capitalize on security vacuum, local resentment against central institutions and the sectarian narrative promoted by Saudi Arabia and Iran as a power politics tool. Notwithstanding escalating “spectacular” attacks against Shia civilians and security/governmental forces, IS didn’t manage to challenge AQAP’s supremacy within the Yemeni jihadi camp so far. Nevertheless, the intra-jihadi rivalry is now on the rise, due to a gradual convergence in operational areas and targets between AQAP and IS.

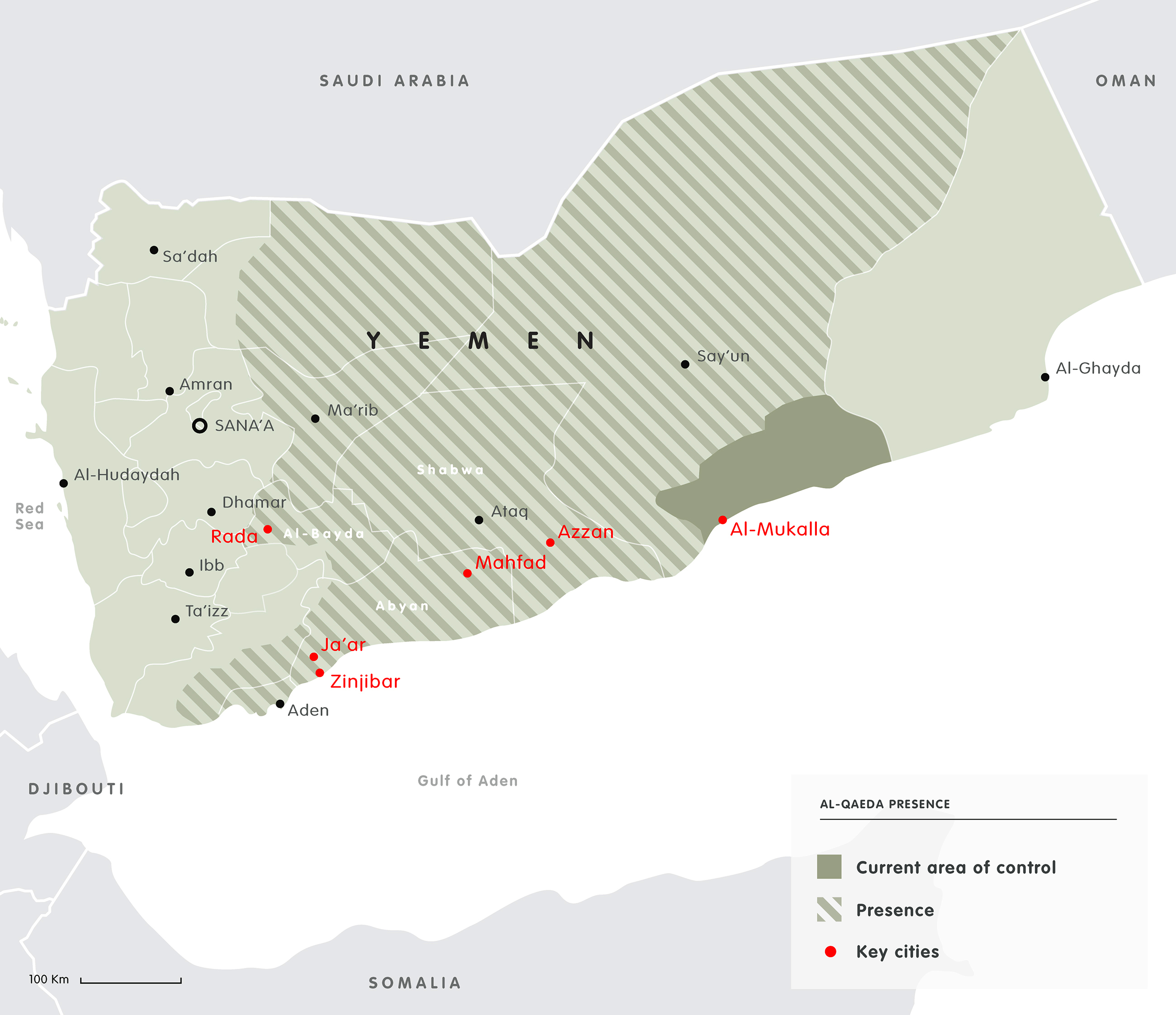

There are at least three factors that disempower IS’s mobilization capabilities in Yemen, underlying AQAP’s intra-jihadi hegemony. Firstly, AQAP was able to establish proto-emirates in the Abyan region (Jaar and Zinjibar provinces) in 2011, before the self-proclamation of so-called Caliphate between Syria and Iraq: that was a vanguard experiment in terms of identity, territoriality and language. Secondly, AQAP and its affiliates, as Ansar al-Shari‘a, rely on a tribal wire of linkages and informal economy’s ties with local population, flourished in remote provinces out of state control. Thirdly, AQAP has elaborated jihadist narratives able to interact effectively with the Yemeni context, so rallying consensus (direct or tacit) among indigenous southern populations, where the shaykh plays a more prominent role if compared with the imam.[1] For instance, AQAP’s English-language publications, as the magazine Inspire, are primarily devoted to foreign audiences: taking into account the high illiteracy rate, the internal dawa is carried out through the ideological use of oral culture and traditional customs, as poetry and songs. These devices find place even in AQAP’s Arabic publications and videos for locals.[2] Adding new complexity to this scenario, AQAP has recently introduced a flexible pattern of governance in southern controlled-cities, as was Mukalla (April 2015-April 2016), searching to merge with the existing social tissue. This community-oriented pattern prioritizes welfare provision and administrative involvement of local population with respect to direct military control and strict shari‘a-implementation, which however remain significant tools of coercion. A compared analysis between AQAP and IS in Yemen contributes to furtherly shed light on the topic.

Genealogies

The bulk of al-Qa’ida in Yemen (renamed AQAP in 2009, when the Saudi and the Yemeni cells merged) was constituted by mujahidin returning from Afghanistan, as in the case of the Aden-Abyan Islamic Army.[3] Ali Abdullah Saleh, Yemen’s president until 2011, was a champion of ambiguity towards local jihadism. At the beginning, he rallied the support of jihadi fighters to combat southerners during the civil war in 1994[4] and then, after 9/11, he signed a security alliance with the United States in the name of the war on terror, choosing to arbitrarily implement securitization policies.[5] Instead, the Yemeni branch of the so-called Islamic State appeared for the first time in the media in November 2014: Ansarullah (the Huthis’ movement) had just seized the capital Sana’a, paving the way for the coup d’état in January 2015. IS in Yemen is predominantly constituted by AQAP’s defectors; beyond Yemenis, Saudi citizens represent the backbone of both jihadi organizations. Since the Eighties, Saudi Arabia has massively contributed to the spread of the Salafi doctrine in Yemen (Sunnis use to follow here the Shafi madhab)[6], through kinship ties and transnational patronage, especially in Hadhramaut, where Sufi Islam is an ancient legacy.

Structures and competition:

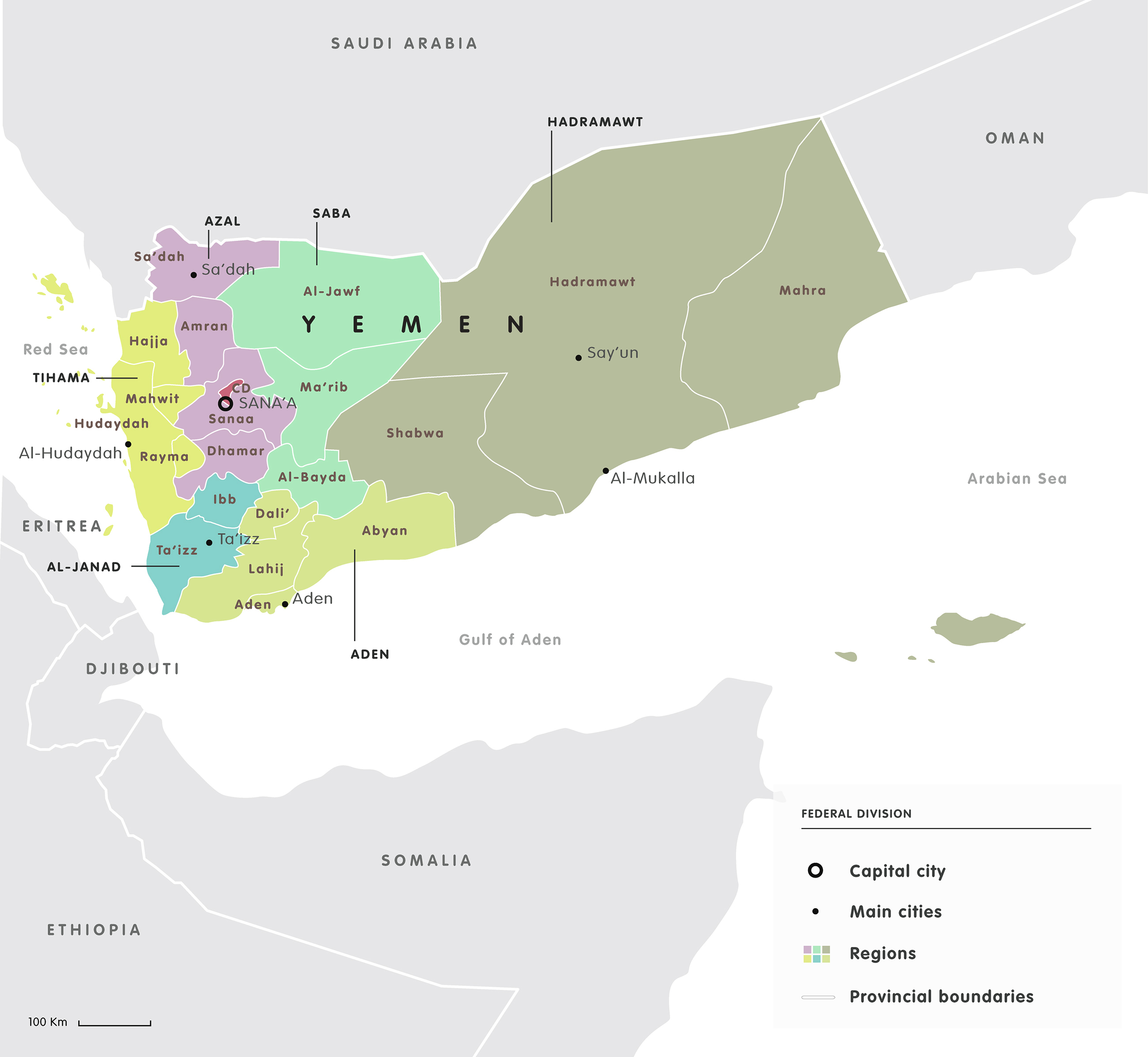

Islamic State in Yemen is organized in small, regionally-based networks, which claim direct responsibility for the attacks in the country. These wilayat are several: Sana’a, Aden-Abyan, Shabwa (the most active and recognizable cells), Ibb-Taiz, Lahij, al-Bayda, Hadhramaut. IS’s wali in Yemen would be a Saudi citizen, as the majority of top-ranking commanders. Saudis prominent role would be generating confrontation within the organization: in two letters dated 15 and 17 December 2015, more than 100 IS’s members asked to al-Baghdadi for the removal of the current wali, denouncing an excessive interpretation of shari‘a.[7]

AQAP shows a more hierarchical structure with respect to the Yemeni cells which pronounced the oath of allegiance to the caliphate. Nasser al-Wuhayshi, killed during a U.S. drone attack in June 2015, was substituted by his deputy Qassim al-Raimi, who soon pledged allegiance (bay’a) to Ayman al-Zawahiri. During the Obama administration, Washington’s counterterrorism strategy has registered an impressive increase of drone strikes, but this tactic did not produce positive outcomes: AQAP remains the most dangerous al-Qa’ida’s node for U.S. homeland and abroad interests. Although many top-AQAP commanders were killed (and then rapidly replaced), the impact of the drone warfare campaign on recruitment was even counterproductive, since recurrent civilian casualties fueled jihadi enrollment among southern, disenfranchised youth. This is especially true for the affiliate Ansar al-Sharia, the ˊchain of transmissionˋ between the terrorist organization and local tribes.

The competition between AQAP and IS regards grassroots recruitment and didn’t involve apical commanders so far: IS-wilayat were mostly created by AQAP’s defectors attracted by higher salaries[8] and a more aggressive attitude with respect to al-Qaeda. In some cases, grey zones between AQAP and IS still persist, as in the case of “Wilaya Hadhramaut”, which could not be necessarily linked to IS. In August 2012, after the temporary emirates’ dismantlement in Abyan, AQAP’s local cell moved to east (Mahfad in Eastern Abyan and Azzan in Shabwa[9]) and may have rebranded itself as Wilaya Hadhramaut. In fact, before the appearance of IS, AQAP used to name its territories with the term wilaya (province), in order to distinguish them from the muhafaza (governorate) belonging to civil states. For instance, in 2011-12, Abyan’s proto-emirates were called wilayat by AQAP, rather than ‘imara (emirate).[10]

Targets and Geography

AQAP prioritizes hard targets, as security forces, and Yemeni government officials, while IS mainly attacks the Huthis and Yemen’s Shia community, without distinctions between hard and soft targets. In May 2012, during the national military parade celebrating the reunified republic, AQAP claimed responsibility for the suicide attack that killed more than 90 soldiers in Sana’a.[11] In March 2015, IS claimed credit for the suicide operations against two Sana’a mosques, Badr and Hashoush, which killed more than 130 believers[12] (Yemeni Sunni and Shia communities use to pray in the same mosques, but in March the capital was already under Ansarullah’s control).

However, this targets categorization becomes day by day more nuanced, even though it remains a salient criterion of analysis. AQAP and IS’s attacks have been following a convergent trend, enhanced by overlapped geographical areas of confrontation (as Aden and recently Mukalla) since the start of the Saudi-led military intervention against Shia militias (the Huthis and former president Saleh’s loyalists, in March 2015) and then of Saudi-Emiratis’ airstrikes against swathes of territory held by jihadists (March 2016). From late 2015 on, IS uses to target government officials and coalition bases, as frequently occurred in Aden, or young police/military recruits in the south. IS began to carry out attacks in Aden when the city was “reconquered” from Shia rebels by the Yemeni army and Sunni militias. In Mukalla, IS (maybe based in in the northern Wadi Hadhramaut sanctuary, not along southern coasts so far) has begun to carry out attacks since AQAP withdraw from the city in April 2016. IS has also criticized AQAP’s decision to avoid armed confrontation in Mukalla with the Yemeni army, Sunni militias and Emirati Presidential Guard’s units.

Aden and Mukalla are now key-cities in Yemen’s battlefield, contested among government and coalition’s forces, pro-independence militias (al-Hiraak in Aden), local tribes and AQAP (supported by some Hadhrami clans in Mukalla). Both cities register growing numbers of Islamic State’s infiltrates. AQAP operates mainly in central and southern Yemen (as Taiz, al-Bayda, Hadhramaut). In al-Bayda, AQAP has entrenched strong alliances with some tribal clans, as the Dhahab tribe (Qayfa confederation) in Rada’a distict: the governor Nayif Saleh Salim al-Qaysi is an AQAP member under U.S. sanctions.[13] After AQAP’s withdrawal from Mukalla, the jihadist presence in al-Mahra, the Yemeni most Eastern region, would be rising.

Narratives

AQAP’s discourse has traditionally combined polemics against the “far enemy” (the United States and the West, Israel and the Jews) with invectives against the “near enemy” (the Yemeni government and the security forces, the Saudi monarchy). In this framework, AQAP has managed to partially exploit southern popular anger towards northern-driven élites, picturing Sana’a’s institutions as shared enemies in order to forge tribal alliances on the ground. In Hadhramaut, AQAP has skillfully played the card of the Hadhrami emancipation from a corrupted and unequal central state, dominated by Saleh’s northern oligarchy and his political heirs. As a matter of fact, AQAP has capitalized on the 2011 Yemeni uprising and the 2013 Hadhrami anti-government protests[14] to prepare Mukalla’s governance experiment. On the other hand, Islamic State in Yemen has bet since the beginning all its ideological resources on sectarian, anti-Shia rhetoric. The Huthis (a minority part of the Zaydi Shia branch, rooted in Saada’s northern fiefdom) have been labeled by IS as the primary enemy -with an eye to expand its leverage in the south- so emphasizing the sectarian narrative already fueled, for power politics purposes, by Saudi Arabia and Iran.[15] The unsolved Yemen’s multilayered conflict risks to empower not only the role of jihadi networks, but also the strength of the sectarian message proposed by IS. AQAP could be tempted to escalate the sectarian tone of its propaganda, in order to compete with IS in recruitment and media, as some statements and small-scale attacks against the Huthis have stressed since 2015.

AQAP’s shifting patterns of governance

AQAP has been repositioning its governance model from a shari‘a-first approach to a community-first posture oriented to power-sharing with local actors. The first type of governance was applied in 2011-12 in some coastal Abyan’s cities (Jaar, Zinjibar). Despite some alliances with indigenous tribes opposed to Sana’a, AQAP (under the banner of the affiliate Ansar al-Shari‘a) self-proclaimed the emirates due to the military vacuum and a spread indifferent mood among locals. AQAP and its network implemented strict shari‘a codes, banned Arab music and the qat (a narcotic leaf which is, at the same time, a local custom and a source of economic survival for many clans), provided basic services to the population, as electricity and water, organizing garbage collection and phone lines connection.[16]

In Abyan, AQAP emphasized ideology on pragmatism, rejecting and trying to replace traditional customs, as qat, in the name of the “Islamic purity”: the aim was to win popular support through the use of coercion rather than consensus. In this framework, the military campaign headed by the Yemeni army, with the ground support of popular committees and U.S. airstrikes, managed to temporarily dismantle the emirates, since locals didn’t oppose government forces. In 2012, Nasser al-Wuhayshi wrote two letters to AQIM’s leader, advising him to gradually implement shari‘a and redesign models of governance not to alienate local population’ sympathy[17]: few years later, Abyan has become a lesson learned for the Yemeni al-Qaeda’s node.

The affiliated Ansar al-Shari‘a seized Mukalla in April 2015: when jihadists took the control of the city, the local army’s unit didn’t intervene to prevent it. As usual, AQAP robbed bank deposits, released prisoners from the jail, abolished taxes. In Mukalla, the capital of the richest Yemeni governorate (oil and gas reserves), AQAP designed a well-functioning “militant economy”, imposing fees on ship traffic and organizing fuel smuggling.[18] Qat was banned, but shari‘a was only intermittently implemented: this time, AQAP demonstrated to be an adaptable, pragmatic organization, deciding (maybe due to some initial protests in the town) to involve locals in administrative tasks. Therefore, AQAP has assured the military control of Mukalla, delegating civil government and its duties to local, tribal bodies: it is not by chance that AQAP rebranded here “Sons of Hadhramaut”, echoing the historical Hadhrami quest for autonomy in order to rally consensus among inhabitants. The pro-AQAP Hadhrami Domestic Council (HDC), established in April 2015, was tasked to provide basic services and pay salaries: it encompasses some tribal shuyyukh, academics and theologians. Differently from what occurred in Abyan in 2011, AQAP didn’t raise the al-Qa’ida black flag in Mukalla. Prioritizing governance on ideology, AQAP has attempted to solve water problems, land disputes between southerners and northerners, reconstructing damaged infrastructures and improving healthcare provisions. The Hadhramaut Tribal Confederacy (HTC), a military and security alliance established by prominent tribes on 2013 to rule the city, has always rejected AQAP and its brand-new banners; however, it has avoided direct confrontation with jihadists so far.[19] In April 2016, at the dawn of the ground offensive to regain Mukalla (organized by the Yemeni army, plus Sunni militias, Emirati Presidential Guard’s units and some U.S. militaries), AQAP decided a strategic withdrawal from the city, following local intermediation. Similarly, a recent AQAP’s statement in Abyan (now rebranded “Sons of Abyan”) warned women and children that the organization would attacked military commanders’ homes. In the long-term, this community-oriented approach risks to be even more menacing for central authorities than the first, shari‘a-driven one, especially in areas when central institutions were absent and unwelcomed since decades.

Conclusions and Perspectives

The ideological and territorial space for AQAP and IS is going to expand without a viable, comprehensive political agreement between the Yemeni government and Shia rebels. Direct, informal talks between the Saudis and Ansarullah (the Huthis’ political movement) have relatively settled violence along the Saudi border, but can’t secure the south from jihadists’ penetration. In this framework, intra-jihadi rivalry between AQAP and IS is likely to increase, because of a gradual convergence trend in operational areas and targets. Notwithstanding this phenomenon, AQAP maintains an hegemonic position within the Yemeni jihadi field with respect to IS. The concept of hegemony, traditionally applied to state actors, is referred here to a non-state actor (AQAP) which acts as a state actor in areas under its control: in these territories, AQAP shows, if compared to IS, superiority in military capabilities and financial resources, plus a certain degree of recognition by local populations. At a micro-level, AQAP’s hegemony is corroborated by three factors: the ˊemirates vanguard projectˋ appeared in 2011, deep tribal linkages and local knowledge, a jihadist narrative able to mix ideological goals with indigenous customs and grievances, so creating an effective story-telling. Open IS-AQAP competition is going to influence AQAP’s language and tactics, fueling sectarian rhetoric and polarizing mixed societies (as in the central Dhamar region). However, AQAP’s new, community-oriented pattern of governance showed in Mukalla has been drawing a line between AQAP and IS directions in Yemen. Such a kind of governance can become even more resilient and difficult to eradicate with respect to the shari‘a-driven model, since it directly bets on Sana’a’s chronical political failures, seeking for local support. From a regional perspective, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates (UAE) started only in March 2016 to conduct airstrikes against jihadi havens in Yemen. Gulf monarchies have changed attitude vis-à-vis AQAP threat in Yemen, as emphasized by Saudi Foreign Minister’s recent interview on Le Figaro, when he pictured jihadists, not Huthis, as the first military coalition’s targets from that moment on.[20] Beyond past ambiguities, Saudis and Emiratis decided to target AQAP and IS cells when they began to heavily threaten the stability of areas reconquered by the recognized government, as Aden. On the contrary, jihadi militias formerly participated in many battles where anti-Huthi forces were engaged.[21] This occurred in central regions as Taiz, al-Bayda, Mareb and in the southern Abyan. Yemen is a “milieu of networks”,[22] open not only towards the Arabian Peninsula and the Gulf, but on the road to the Horn of Africa too: in this sense, Aden’s security remains critical.[23] Aden (and to a lesser extent Mukalla) is a choke-point for trade and energy and its instability could also provoke a resurgence of piracy in the Gulf of Aden. Moreover, the future implementation of the federal reform project, contested by many southern regional actors (for instance in Hadhramaut and al-Mahra), could furtherly turn local tribes towards AQAP.[24]

References

[1] Elisabeth Kendall, “Al-Qa’ida and Islamic State in Yemen: A Battle for local audiences”, in Simon Staffell-Akil Awan (eds), Jihadism Trasformed. Al-Qaeda and Islamic State’s Global battle of ideas, Oxford, University of Oxford, 2016.

[2] As the new newspaper Al-Masra and the media outlet Wikalat al-Athir, focused on welfare.

[3] The Aden-Abyan Islamic Army was organized in the 1990’s by Abu Hasan Zayn al-Abadin al- Mihdhar, a Yemeni commander from Shabwa. The militia supported Saleh-led government against socialists in the south. Gregory D. Johnsen, The Resiliency of Yemen’s Aden-Abyan Islamic Army, Terrorism Monitor, The Jamestown Foundation, July 13, 2006.

[4] Laurent Bonnefoy, “Varieties of Islamism in Yemen: The Logic of Integration Under Pressure”, Middle East Review of International Affairs 13, 1, 2009.

[5] Franck Mermier, De la répression antiterroriste à la répression antidémocratique, Le Monde, 7 gennaio 2010.

[6] Shafeism is a synthesis between two schools of Islamic jurisprudence (madahib): malikism, based on conservative tradition, and hanafism, which emphasizes the role of reason in religious understanding.

[7] Emily Estelle, 2015 Yemen Crisis Situation Report: December 30, The Critical Threats Project, America Enterprise Institute

[8] Katherine Zimmerman-Jon Diamond, Challenging the Yemeni State: ISIS in Aden and al Mukalla, The Critical Threats Project, American Enterprise Institute, June 9, 2016.

[9] Andrew Michaels-Sakhr Ayyash, AQAP’s Resilience in Yemen, Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, September 24, 2013.

[10] Elisabeth Kendall, op. cit.

[11] Al-Arabiya, Al-Qaeda claims bombing that killed nearly 100 Yemeni soldiers, May 21, 2012.

[12] BBC News, Yemen Crisis, Islamic State claims Sanaa mosque attacks, March 21, 2015.

[13] Katherine Zimmerman, A New Model for Defeating al-Qaeda in Yemen, American Enterprise Institute, September 2015; Bailey Palmer, 2016 Yemen Crisis Situation Report: June 14, The Critical Threats Project, American Enterprise Institute.

[14] Haykal Bafana, Hadhramaut: Rebellion, Federalism or Independence in Yemen?, Muftah, April 22, 2014.

[15] Jeff Colgan, How sectarianism shapes Yemen’s war, The Mokey Cage Blog, The Washington Post, April 13, 2015.

[16] Robin Sincox, Ansar al-Sharia and Governance in Southern Yemen, Hudson Institute, December 27, 2013.

[17] Michael Horton, Capitalizing on Chaos: AQAP Advances in Yemen, Terrorism Monitor, The Jamestown Foundation, February 19, 2016.

[18] Yara Bayoumi-Noah Browning-Mohammed Ghobari, How Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen has made al Qaeda stronger- and richer, Reuters, April 8, 2016.

[19] Katherine Zimmerman, A New Model for Defeating al-Qaeda in Yemen, op.cit.

[20] Georges Malbrunot, L’Arabie saoudite change de priorité au Yémen, (interview with Adel al-Jubeir), May 10, 2016, Le Figaro.

[21] Anti-Huthi forces refer to a loose coalition of Islah’s militias (the party which encompasses Yemeni Muslim Brothers and Salafis), al-Hiraak pro-independence militants, popular committees and other tribal warriors.

[22] Anna Maria Medici, “A Weak State’s Awakening”, in Anna Maria Medici (ed), After The Yemeni Spring: A Survey on the Transition, Milano-Udine, Mimesis, 2012.

[23] Nadwa al-Dawsari, Rethinking Yemen’s Stability. Why Stabilizing Yemen Must Start in Aden, Project on Middle East Democracy (POMED), October 29, 2015; on Aden’s regional (in)security complex, Eleonora Ardemagni, The Yemeni Conflict. Genealogy, Game-Changers and Regional Implications, Italian Institute for International Political Studies (ISPI), Analysis, n° 294, April 2016.

[24] Eleonora Ardemagni, Beyond the North/South Narrative: Conflict and Federalism in Eastern Yemen, in “Reflections from Yemen: narratives of Resilience”, LSE Middle East Centre Blog, May 16, 2016.