Since October 2024, ITSTIME has been monitoring and analysing the presence of pro-Islamic State (IS) propaganda content on the TikTok application. The research undertaken made it possible to initially identify more than 180 seed accounts, which were used to reconstruct a network of more than 140,000 users.

Furthermore, it was possible to detect (currently) different typologies of users active or not in the spreading of IS propaganda material and to understand how TikTok stands within the entire pro-IS propaganda ecosystem.

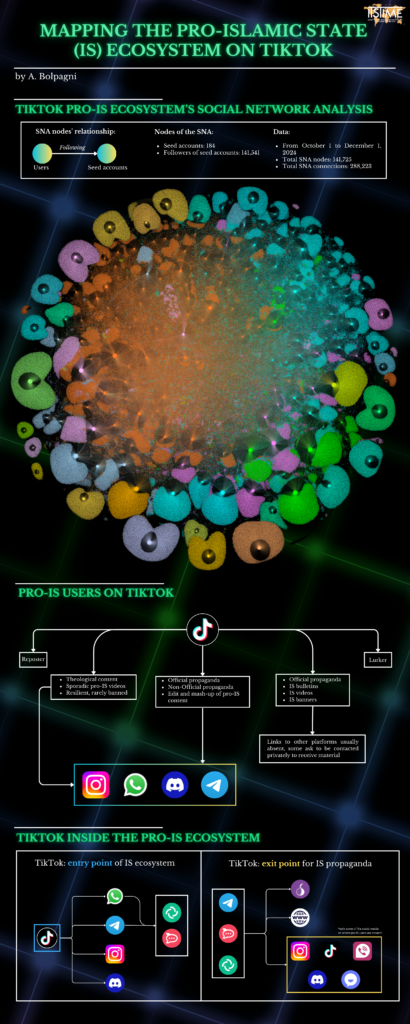

Aimed at understanding the potential extension of the pro-IS network on TikTok, the seed accounts selected to create a preliminary Social Network Analysis (SNA) were the users who directly shared IS-related material on their account, i.e. institutional propaganda material and propaganda material produced by the Ansar Production. The network of pro-IS users was then reconstructed through an SNA that relates seed accounts and their followers through the action of following.

Currently, six types of shared material can be outlined, such as IS institutional propaganda video, images, and documents, nasheed produced by institutional media houses, spontaneous translations of institutional IS material, and spontaneous propaganda inspired by institutional material. Beyond the network as a whole, from an analysis of the shared material, it was possible to delineate 5 (currently) categories of users within the pro-IS ecosystem on TikTok.

From the propaganda structure point of view, within the pro-IS digital ecosystem, TikTok stands simultaneously as an entry point for pro-IS individuals and as an exit point for IS and/or pro-IS propaganda stream. TikTok is thus an entry point since a large part of the application’s users are young individuals, who are then channelled to platforms where the pro-IS ecosystem is already structured. Furthermore, the exit point role of IS propaganda is complementary to the entry point role. Given the large presence of young individuals who can be radicalised, the propaganda assumes a high degree of adaptability so as to reach a level of greater usability in relation to the users to whom it is addressed. Finally, TikTok can not only take on the role of a digital recruitment platform but also social media to conduct da’wa, namely the action of proselytising in Islam.

Albeit often intercepted before carrying out an attack, the presence of increasingly young attackers requires that platforms such as TikTok receive more attention and constant monitoring. Even more so when one considers that IS’s focus on young people as the target of its propaganda and radicalisation has been growing in recent years.